Carnaroli rice was born in 1945 through a mix between the “Vialone” and the “Leoncino”, by the rice farmer Angelo De Vecchi from Paullo (Milan). The name comes from one of his collaborators, this Carnaroli; this man was descouraged because of the poor results of the cultivation; so one day he said to De Vecchi: “Sir what should we do?”. The rice farmer replied: “Let’s go on, if we find the quality that I mean, I’ll call that rice with your name.”

Carnaroli rice is a “LONG A” type and it’s a JAPONICA variety which has 165 days of growing season.

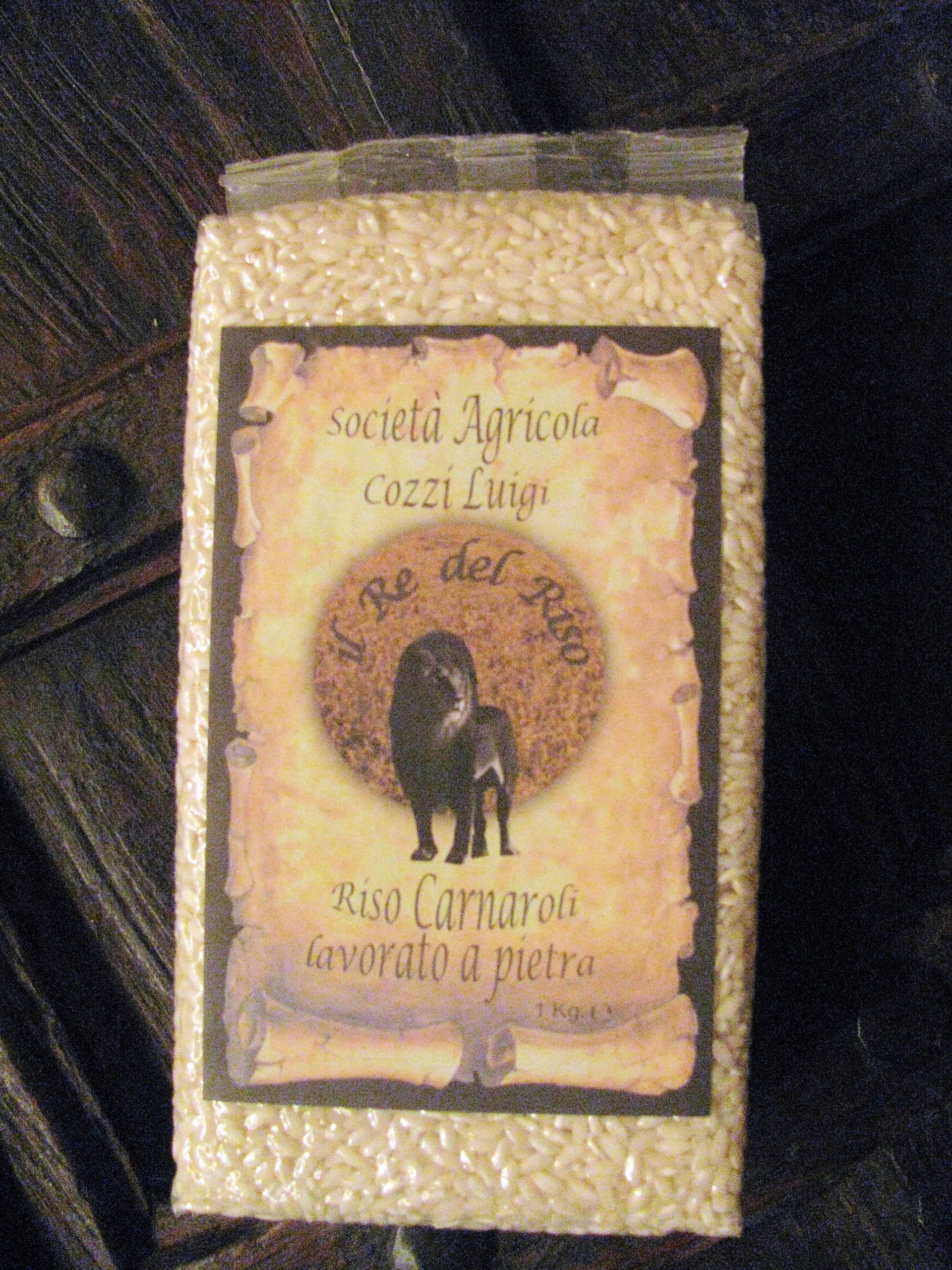

Carnaroli rice is traditionally used to prepare “risotto” and it is characterized by great content of amylose, very firmer consistency and long-grain. Thanks to these characteristics, Carnaroli rice takes better cooking than other varieties of rice, considerating the slow cooking required to prepare “risotto”. This rice belongs to the class “superfine rice” and it’s often called the “king of rice”.

As unfortunately happens also to other well known varieties of rice, for industrial market reasons, under the name Carnaroli we can also find varieties belonging to the same product group (for example Carnise, Karnak, Keope, Caravaggio, Poseidone varieties) but that are obtained by Carnaroli rice through a genetic modification: the differences are undeniable both in cooking and in eating. Same form, but different substance …. It’s therefore not easy that a package of Carnaroli rice really contains this variety and not other surrogate.

An important factor for Carnaroli lovers is to find Carnaroli rice produced from certified seed. Respecting the consumer and the ancient agricultural tradition, “Società Agricola Luigi Cozzi” uses only certified seed, in order to produce a limited production bringing on your tables a top quality product. The traceability and authenticity guarantee given by seed is crucial to distinguish the peculiarities of this rice variety. Indeed, thanks to the use of certified seed, renewed every year in the certification cycle provided by ENSE (Elected Seeds National Agency) you can be sure to eat the authentic taste of Carnaroli rice.

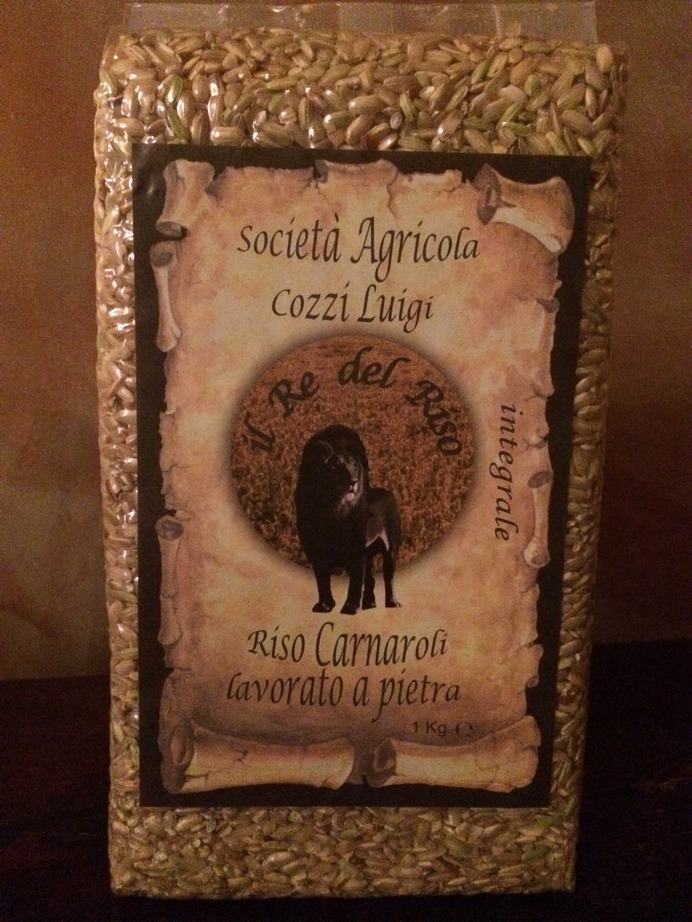

Whole grain rice also commonly known as brown rice; its grain, consisting of the hull and germ, is simply dehusked, that is the outer hull is removed through a roller husker: the rice grain is still coated in a fine silvery layer.

Consumers like brown rice because it preserves the pericarp and germ, therefore retaining higher amounts of nutrients compared to white rice. It takes longer to cook (around 40 minutes) because of the pericarp which restricts the absorption of water.

Whole grain rice is made up of 12% water, 7% proteins, 69.2% carbohydrates, as well as dietary fibre, fats, sugars, and minerals such as iron, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, selenium, manganese, copper, and zinc. Whole grain rice also contains some B vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B5, and B6), vitamin E, and vitamins K and J, traces of niacin, that is a B vitamin which helps protect the cardio-circulatory system and the gastrointestinal tract.

Whole grain rice is also rich in antioxidants and fibre which help improve the function of the intestine.

Amino acids such as alanine, arginine, cysteine, glutamic acid, asparagine, valine, tryptophan, leucine, lysine, glycine, serine and tyrosine are also present.

Whole grain rice also contains a fairly high amount of selenium, as well as manganese (a cup of rice provides 80% of the daily requirement) which help maintain a healthy nervous and reproductive system.

Whole grain rice helps keep blood sugar levels stable and is extremely easy to digest; the energy accumulated by eating whole grain rice is used up more gradually during the course of the day, without the build-up of fatty deposits.

The inconsistent colour of our Carnaroli certified whole grain rice and the presence of wild rice (red rice grain) demonstrate that it is grown in the traditional, natural way only using certified seeds and not genetically modified seeds, which always have a perfectly uniform colour (clearfield rice such as the Carnise, Karnak, Keope, Caravaggio, Poseidone and Leonidas CL varieties…).

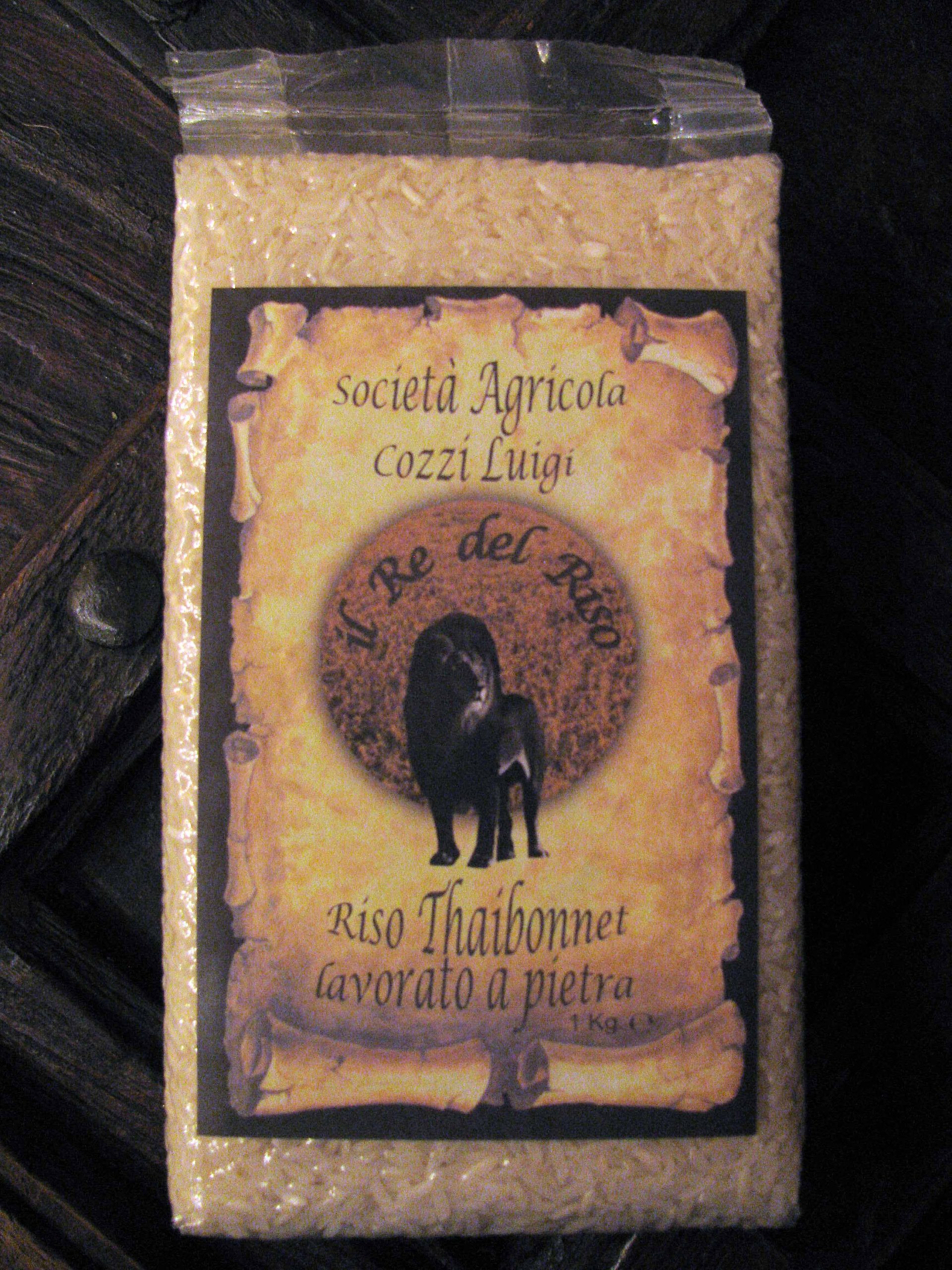

Thaibonnet rice is a “LONG B” rice and it’s an INDICA variety which has a very long growing season.

It ‘s a crystalline rice and it’s similar to oriental rice, but typically Italian. Its main feature is the minimum starch release during cooking, which helps keeping the grains separate. The shape of its grain (very long and tapered), and the lack of stickiness, make it an ideal ingredient for paella, rice salads and side dishes. It is absolutely not recommended, however, to use it for cooking “risotto” because it doesn’t mix, and it is equally unsuitable for the preparation of desserts.

The boiling time to have a firm rice is less than 13 minutes, because traditionally you want a final product perfectly grainy. And in that sense, this variety allows exceptional performances, because this rice has high resistance to cooking and it’s very good for recipes in which it’s necessary that grains remain intact and divided among themselves.

RICE LIFE CYCLE

RICE FIELDS ORIGINS. The various flat parts of the fields are never in the same level. In the past, before the mechanization, rice farmers used to adapt to ground conditions which usually had an irregular altimetry. Therefore, rice farmers built many levees following the natural ground curves which had levels at different heights of even a few centimeters. This lead to the development of the formation of many small and irregular levees and the division of the ground into several small fields on different levels. Consequently, people could level the ground with inexpensive operations. As mechanization spread, rice farmers had the need to work on large surfaces in order to conveniently use the machineries for the different cultivation operations. We adjusted our ground using very modern and rational concepts to make large surface movement using machineries (reclamation).

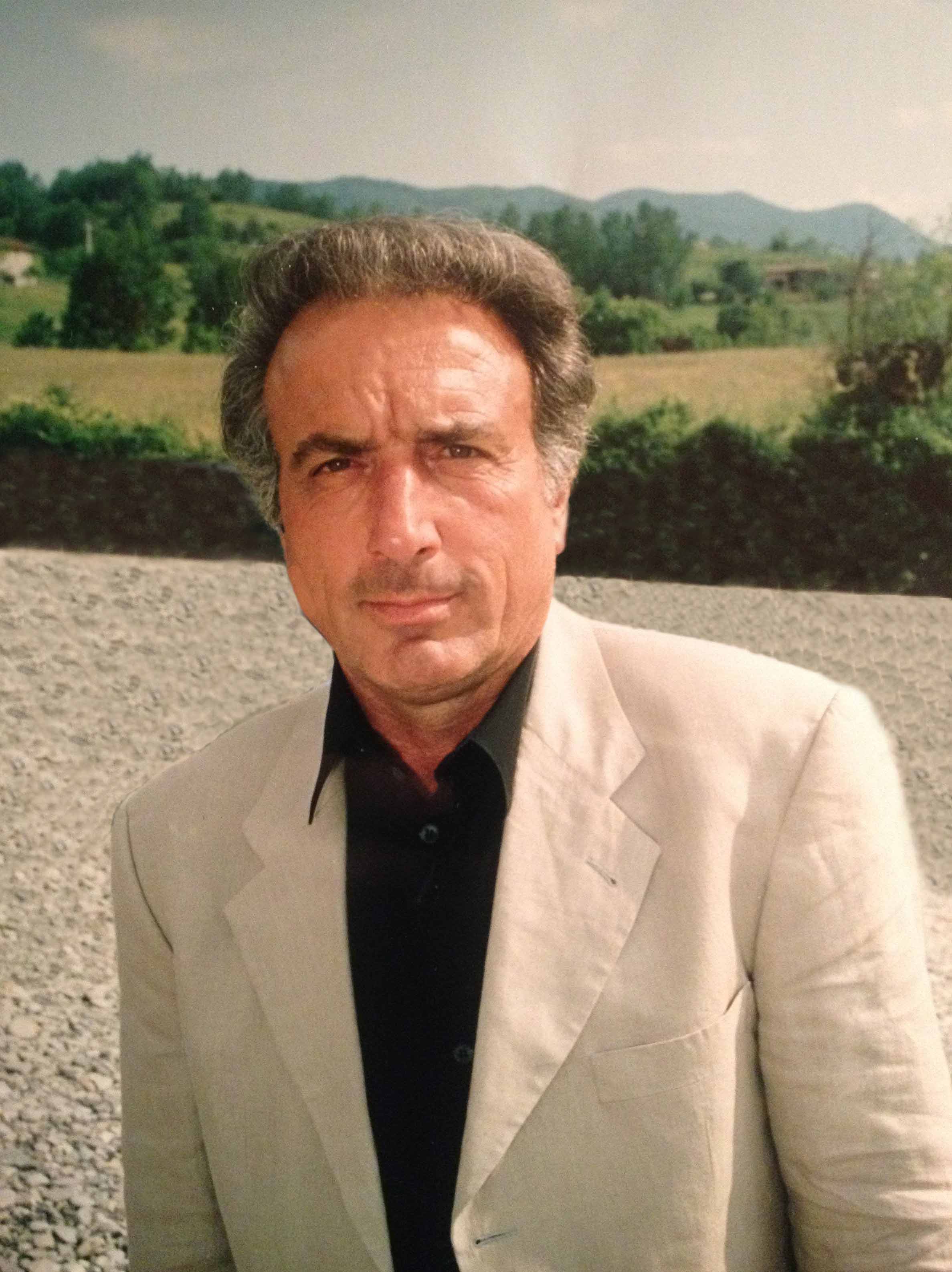

Our fields (Cascina Cineroli and Recetto’s fields) were designed by the quick-witted, creative and immaginative mind of Luigi Cozzi, who could combine the most modern mechanization with traditional agriculture dictates. Luigi Cozzi was shrewd and strong-willed, he had a deep passion for the land; he betted on his dream and he became the pioneer of the wide rice field (“camere”).

Thanks to Luigi Cozzi, our fields are separated between them by very tough and pressed levees to avoid landslides; so the whole land has stronger levees, embankments downstream, service roads and the ducts which are used to flood and collect sewage. The clear and running water must grout the field and must flow in the next field; for this reason, the fields are plowed by small ditches which cross the fields both vertically and horizzontally; therefore these ditches release and drain the water. The water comes from the ditch into the first field through very covered nozzle entrance to avoid excessive erosion becouse of flowing water; the nozzle downstream is connected with the nozzle entrance by a groove which facilitates flowing and gets the water into the next field: rice fields are flooded cascade one after the other.

The outcome is a squared sea, a landscape that seems to be made with many small lakes bordered by simple levees: if you look more carefully, you can see a complex, ingenious and meticulously structured system.

Luigi Cozzi founder of

“il Re del Riso”

After ploughing, the earth must be levelled to obtain a perfectly flat “surface”, without height differences or hollows which may hamper efficient water management. One of the key conditions for achieving the best results in rice growing, both in terms of quality and efficiency, is to prepare a completely level seedbed.

Uneven ground, in fact, prevents effective irrigation, doesn’t allow the uniform application of fertilisers and impedes the plants from tillering regularly.

In the past, water was added to the rice field as a levelling aid, to help the farmer identify any uneven ground, which was then broken up by women with hoes, while a harrow or wooden board drawn by a horse was used to level the land. This was a strenuous operation as it was carried out in bare feet in the cold waters of early of spring.

Today, levelling is done on dry land by means of a laser-controlled levelling system: a transmitter mounted on a tripod sends laser signals to a receiver attached to the tractor. As a result, the blade automatically moves up and down to perfectly level the soil.

At this stage it is important to strengthen the banks to avoid landslips and it is essential to clean ditches and streams as well as repairing the sluices which allow the flow and adjustment of the water to take account of the different levels of the various rice fields.

There are several reasons for carrying out this fertilisation:

1) to address any potential deficiency in the soil, with reference to the individual nutrients needed to grow a healthy, resilient plant; 2) to increase the fertility potential of the soil; 3) to compensate for the removal of nutrients following the production and harvesting of the rice, taking into account the inevitable losses; 4) to restore the ratio between the various nutrients required for keeping the soil fertile in proportion to their use by the plant; 5) to increase the commodity value, as well as the biological value, of the rice.

Nowadays, the harrow is pulled by a tractor instead. Harrowing is an important operation as it aerates the soil, allows the roots to breathe, prepares the soil for the introduction of fertilisers, and facilitates the subsequent seeding of rice.

Rice cultivation is therefore facilitated by having a plentiful supply of water.

The Piemonte region has a large area of rice-growing fields thanks to the availability of water and natural water sources, as well as the presence of artificial irrigation channels, among which the most important is the Cavour Canal, a major water infrastructure, 80 km long, which starts out straight, bends where necessary, and passes underneath a number of rivers. This irrigation network, some sections of which were designed by Leonardo, dates back to the 15th Century. Its main channel, the Cavour Canal, is named after the Count Camillo Benso of Cavour, who was the Piemonte government Prime Minister at the time and was one of the promoters of this major construction work, which began in early 1863 and was completed in 1866. Fourteen thousand men built, in less than three years, a complex system of bricks and natural stone, which would enable the irrigation of the land and which still today is considered as the jewel in the crown of hydraulic engineering in Italy and Europe: a colossal irrigation project which laid the ground for the future “golden triangle of rice”. The Cavour Canal starts off from the River Po in Chivasso (entrance building), flows into the waters of the river Dora Baltea, crosses the plain in the Vercelli area, passes underneath the river Sesia and goes across the plain in the Novara area, and ends up in the river Ticino.

Originating at 2.500 m on Mount Rosa, from the glacier by the same name, the river Sesia (more commonly known as “The Sesia”) flows down the Sesia Valley, is enriched by the waters of numerous streams, and constitutes a natural border between the provinces of Novara and Vercelli. It is approximately 140 Km long and is one of the longest rivers in the Piemonte region.

The Canal, which takes water mainly from the river Po, the Sesia, and Lake Maggiore, serves with its tributaries an irrigation network extending over 20.000 km. The network is managed by the “Associazioni di Irrigazione Est e Ovest Sesia” (East and West Sesia Irrigation Associations) through the lock-keepers who control the channels down to the last millimetre and supply the required amount of water to each farmer. By means of flood irrigation and basin irrigation, the East and West Sesia take water from the rivers, allow it to flow into the network and return it to the rivers without wasting a single drop. Man has channelled water through a number of millraces, canals, and channels which flow one into the other and into the rice fields to create a controlled irrigation system: the fields are flooded using small sluices, dykes, or embankments which divide the fields into sections. In this way it is possible to have running, non-stagnant water in the rice fields so as to prevent the formation of the so-called “cream” on the surface.

The fields are submerged and there is a continuous flow of water: first you see a sea divided up into grids, then the young plants beginning to appear.

This method, which has become very cumbersome, has been abandoned and today direct seeding is the only method used in rice-growing in Italy. Seeding is carried out directly in the previously flooded rice fields. This takes place in April, just after the rice fields have been flooded.

The time chosen for seeding is paramount: if it is too early there is a risk that the changeable weather in April may bring days when temperatures are still very low. Moreover, the water used to flood the rice fields comes mainly from the Dora Baltea and from the tributaries of this glacial river the temperature of which, in April, is around 10 degrees.

The water in the rice field helps to regulate the temperature during the first stages of the young plant’s development: it compensates for extreme temperature variations between day and night, by retaining the warmth from the sun built up on a spring day during the still cool night hours. Water can be added or removed quickly in response to weather changes in order to inhibit algae growth or other aquatic plants that cause infestation, to kill parasites, and to encourage rice growth.

Today we know precisely how much time it takes from seeding to harvesting for all the varieties of rice. Also, and this is also the case with late-harvest varieties, seeding does not normally take place beyond the first ten days in May. This is in order to avoid harvesting rice in late autumn, with all the risks associated with bad weather and rain.

In order to combat the “weedy rice” (“crodo”) variety, late seeding from the second to the third 10-day period in May has been the most widespread method over the last few years. This technique is also recommended on account of the increasingly controlled use of water based on a “gradual irrigation” of the area. In fact late seeding allows for, among other things, the application of the “false seeding” technique, an ancient agronomic practice which involves preparing and irrigating the seeds as in normal seeding but, in reality, the seeds are not sown into the soil. In this way the seeds of invasive plants which are also present in rice fields, such as weedy rice (“crodo”), are stimulated and later removed mechanically by means of a harrow.

Prior to seeding, paddy rice seeds are first left in water to revive them and make them heavier so that, instead of floating near the surface, they land on the bottom. In this way the risk of the seeds that would otherwise struggle to take root floating away is reduced, and the future young plants are sure to be distributed evenly. Seeding in water is known as “broadcast seeding”, because the seeds are scattered randomly using a mechanical rotating plate. Today “broadcast seeding” is carried out by means of a GPS satellite system which guarantees precision and reduces seed loss.

The rice seed is an embryo which contains all the minerals that a plant requires in the first stage of its growth; the seed in water, after about eight days, swells up and develops a “tiny root” which grows downwards and a stem which grows upwards. At this stage the rice field is drained in order to allow the rice plant to properly take root in the soil. Later the soil is flooded again and from this moment on, the rice field is regularly and expertly drained and irrigated.

Unfortunately, dry seeding causes the proliferation of the “weedy rice” (“crodo”) species, which is very similar to rice. One of the main characteristics of “weedy rice” is the tendency of the grain to fall off the panicle to the ground before harvest. The weedy rice plant can be identified as it is taller than the cultivated rice plant and red in colour. As the grain ripens, it falls off the stalk, making it impossible to pick. The problem is that it ripens before standard rice, its seeds shatter, fall to the ground and can germinate for several years causing an unmanageable infestation of the rice field. This leads to a loss of production, which in the case of a large weedy rice infestation can result in a drastic reduction in the quantity and quality of the harvest.

Dry seeding, however, enables rice growers to obtain good results in rice fields that experience problems with fermentation due to the decomposition of the organic matter, as well as the excessive presence of algae, tadpole shrimps or the aquatic weevil. Moreover, it hinders or delays the development of invasive aquatic plants (e.g. Alisma, Cyperus difformis, Heteranthera …), reduces the release into the atmosphere of water vapour, and jeopardises the yield of the taller varieties (such as the Carnaroli rice, which grows higher than standard rice).

An indiscriminate and excessive use of chemicals over time, not only increases the resistance of the weeds, but also encourages the growth of new species, which are very hard to eliminate. This is why some companies are returning to the method of hand weeding.

In fact, in the past, this type of work was done by “mondine” (women rice field workers) or “mondariso” (rice weeders – from the verb “mondare”, which means to clean), seasonal workers who worked in the rice fields. This work consisted of transplanting small plants in the rice fields (“trapiantè” in the dialect of the Piedmont region) and in cleaning (“mundè”) or uprooting the plants which infested the rice fields and suppressed the normal growth of the rice.

Cleaning rice is a complex and strenuous job: the women were bent over with their feet and hands in the water, walking side by side, pulling out the weeds, which often look very similar to the rice plants themselves, but which must be identified at a glance. In the past, this work was done in groups and each group had one male or female worker who was the group’s supervisor, “the boss or the lady boss”.

Cleaning starts approximately one month after seeding and usually lasts from 45 to 50 days, until the end of June, but can continue, in exceptional cases, until the end of July.

The life-cycle of rice undergoes various different stages: germination, tillering, heading, flowering, fertilisation and maturity.

The seed can only germinate in optimal temperature and oxygenation conditions; during the GERMINATION STAGE the amount of oxygen available and the temperature, which must not fall below 12°C, are vital factors. When the seed is sown in water there is a lack of oxygen as water flows within the parcel. For this reason, after the plumule has been formed, the parcel must be dried so that the tap root binds into the soil and the germination can continue. Drying off the rooting ensures the strengthening and stretching of the roots, the better nutrition of the plant and greater vegetative development.

This is perhaps the most delicate stage of the entire cultivation process. In fact, the seed is still only loosely anchored to the ground and at the mercy of the waves and currents inside the parcel. There are many factors that could detach it from the soil and carry it elsewhere: the wind, the masses of algae moving about and the miniscule crustaceans on the bottom. This stage is completed when the plant has formed the second/third leaf.

The next phase is called TILLERING in which secondary tillers are formed: within 40/70 days since germination, secondary shoots and adventitious roots gradually appear and the paddy field transforms from a lake into a green meadow. During this stage, the culms develop first from the buds at the base of the leaves and then from the buds on the already developed culms. The number of culms that develop varies according to the varieties of the rice, but it is also affected by cultivation practices and, in particular, the density of sowing and fertilization.

During this period – in June – the HEADING stage begins when the culm internodes lengthen, the leaves grow and the inflorescence develops.

Rice, in addition to being demanding in terms of temperature, is very sensitive to daily temperature changes.

In this period the partial submersion of the plant is very useful. During the night, the water gives back some of the heat accumulated during the day, thus performing the “thermal flywheel” effect, particularly important at our latitudes, to ensure the spikelets’ fertility and, consequently, an ample harvest.

The heading stage concludes with the formation of the first inflorescences and the beginning of the plant’s reproduction period.

In July and August the FERTILISATION takes place, mainly via self-pollination. The flowering and pollination process starts from the top of the spikelet and proceeds downwards. The rice flower opens 90-100 days after seed germination, in July, and is protected from glumes and husks; the flower contains 6 styles that carry anthers (the male organ) which in turn contain pollen; at the base of the flower is the pistil (the female organ) formed by the ovary and the stigma on which the pollen falls. The fertilisation lasts 5 to 60 minutes: the pollen is collected from the ovule with the help of the plumules and from then on (in August) the caryopsis starts to form and matures between September and October, depending on the variety. During fertilisation, the air temperature and humidity are critical.

The last stage is that of MATURITY, when the ovary is transformed into a coated caryopsis: the grain begins to receive and accumulate nutritional substances. Its milky consistency becomes waxy and, eventually, vitreous. The maturation of the panicle also starts from the top down, and finishes in September/October, depending on the variety.

Night concert in paddy field

WHY SHOULD YOU GIVE RICE AS A GIFT?

The use of throwing rice on bride and groom originates from Chinese tradition: an ancient legend says that the Good Genius was moved with compassion when he saw the farmers affected by a serious dearth, so he asked farmers to irrigate the ground where he had sheded his teeth with river water. The water turned the teeth into seeds from which thousands of rice plants germinated and the peeled fruits of rice plants recalled the Good Genius’s white teeth: rice plants fed all the population forever. Since then the rice became a symbol of abundance and prosperity and throwing rice on bride and groom is equivalent to wish them abundance, prosperity, fertility and a future of happiness and accomplishment.

In China rice planting really became a state ceremony, where Emperor himself took part with princes and dignitaries: the richly dressed emperor entered into rice fields depending on the temple and he made four grooves with a decorated plow pulled by a pair of white oxen; princes imitated the emperor because they had to draw a growing number of grooves in inverse proportion to their nobility degree. The noble harvest of that field needed for the offerings, for special occasions and for souls of famous dead people.

In our culture, rice also has a large number of symbolic associations. In ITALY, it is customary to throw rice over the newly-weds just after the ceremony outside the church in order to bring them both fertility and prosperity.

This tradition dates back to both an ancient Greek ritual according to which, in order to ask the gods to grant the couple the gift of fertility they were showered with rice, and to a Roman custom: throwing rice over the newly weds outside the church as a way of wishing the couple the gift of fertility. Rice, easier to find than wheat and also more aesthetically pleasing, was accompanied by tiny stones – which were later replaced by sugared almonds and coins – in order to cast out any demons.

The Romans, however, regarded it as so rare and precious that they were willing to pay a high price for it, and married women used it for their beauty masks, while Galen recommended it as a treatment for a variety of diseases. Its use in the kitchen, however, was rare, except for gladiators who ate it because it was nutritious and kept them in good shape to endure their training school (ludus), and to participate in the ludi (non-violent spectacles such as the plays and chariot races that took place during religious festivals) but, above all, to prepare themselves for the munera, the deadly gladiator combats which took place in amphitheatres and, prior to the construction of amphitheatres, in the forum or in suitably adapted settings. Gladiators had to follow a special diet prepared by the lanista, who was the owner of the gladiator training school they belonged to (or familia) in order to ensure their body was in perfect condition. The Romans regarded rice as one of the most nutritious cereals, light and easy to digest, which made them stronger and improved their performance without making them put on weight and which was therefore essential to achieve the perfect sculptural form required of a gladiator.

In KOREA a typical farming village is always situated next to a rice field, at the foot of the mountains, because its inhabitants must be able to care for the rice plants day in day out. Otherwise, if the plants are neglected, it is thought they will perish just like abandoned children.

In most villages in Korea the villagers have a band which plays music during harvesting, festivals and ritual ceremonies in honour of the village deity, which take place according to the moon calendar, on the first day of the full moon, when many villages, especially in the southern part of the peninsula organise tugs of war.

Rice, especially in the villages, is regarded as the household deity, whose main symbol is a glass jar full of rice, placed in the courtyard or inside the house.

Once a year, housewives offer cakes made of rice to the deity, asking it to grant them a good harvest for their farms and good health for their families.

To be continued next month